Gold Rush Players

Black Bart

“I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tred

You fine-haired sons of bitches.” |

Black Bart, The PO8 |

On August 3 of 1877, a stage was making its way over the low hills between Point Arenas and

Duncan’s Mills on the Russian River when a lone figure suddenly appeared in the middle of the

road. Wearing a long linen duster and masked with a flour sack, the bandit pointed a

double-barreled shotgun at the driver and said, in a deep and resonant voice, “Throw down the

box!” When the posse arrived later, all they found was a waybill with the above verse

painstakingly written out on its back, each line in a different hand.

Almost a year later, on July 25 of 1878, the PO8 struck again. As the stage from Quincy to

Oroville slowed to make a difficult turn along the Feather River, the masked man stepped out of

the bushes and asked that the box be thrown down. His spoils included $379 in coin, a silver

watch, and a diamond ring. Once again, when the posse reached the scene, all they found was a

poem:

“Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat,

And everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will I’ll try it on,

My condition can’t be worse;

And if there’s money in that box

’Tis munny in my purse!” |

Once again the lines were written in varying hands and the work signed “Black Bart, The PO8.”

In order to make the highways safe once again, Governor William Irwin posted a $300 reward for

the capture of the bandit, to which Wells Fargo & Co. added another $300. Another $200 was

contributed by the postal authorities. The reward went unclaimed for five years, during which

Black Bart seemingly robbed at will. Often laying low for several months, Bart would suddenly go

on a spree and rob three or four stages in as many weeks, and then vanish without a trace. Black

Bart’s talent for covering great distances on foot in impossibly short times (described as a

“thorough mountaineer and a good walker” in a Wells Fargo circular), was no doubt a great asset

in his life as a highwayman.

The morning of November 3, 1883, proved cold and clear as Reason E. McConnell drove his stage

towards Copperopolis. His only passenger that morning was young Jimmy Rolleri, and his only cargo

was the Wells Fargo chest fastened securely to the floor of the stage. Fastened securely because

along with the $550 in gold coin and some three and a quarter ounces of gold dust, the box

contained 228 ounces of gold amalgam from the mill at the Patterson Mine. As the stage slowed

down at the approach of Funk Hill, Jimmy jumped off the stage with his Henry rifle to do some

hunting, planning to meet the stage on the other side of the hill. As the stage neared the top of

the hill, a rustle in the brush made McConnell turn his head. He found himself looking straight

into the muzzle of a double-barreled shotgun.

You see, Black Bart knew about the amalgam. Ordering McConnell to unhitch the team and walk

them up the hill, Bart then entered the stage and commenced to break open the chest. Meanwhile,

Jimmy somehow managed to meet McConnell away from the stage. The two took cover and watched as

Black Bart backed out of the stage with his loot. McConnell then “seized the rifle from the boy

and opened fire on the robber.” He missed, twice, after which Jimmy took the rifle and fired,

causing Bart to stumble before disappearing into the brush.

Sheriff Ben Thorn of Calaveras County reached the holdup site that afternoon and organized

the posse to search for clues. Among the items found was a small round derby hat, two paper bags

containing crackers and granulated sugar, a leather case for a pair of field glasses, a belt, a

quartz magnifying glass, a razor, a handkerchief full of buckshot, three dirty linen cuffs, and

two flour sacks. Black Bart would have undoubtedly taken his belongings with him had he not been

run off by the Henry rifle.

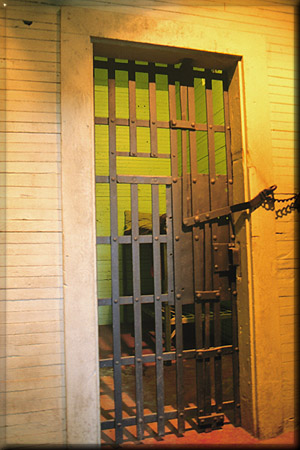

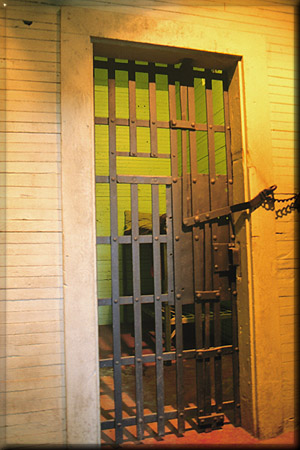

Black Bart's Jail Cell | | The handkerchief full of buckshot proved to be Bart’s downfall, for in one corner were four

small letters: F.X.O.7., a laundry’s identifying marks. Sheriff Thorn took the evidence to Wells

Fargo detective J. B. Hume in San Francisco, whereupon Hume turned the handkerchief over to

special operative Harry Morse who immediately went to work on tracing the laundry mark. A week

later, on November 12, the laundry was found and the owner of the handkerchief identified as one

Charles E. Bolton.

Bart was arrested and after lengthy questioning decided to confess to the robbery and show

his captors where he had hidden the amalgam, hoping this would make it easier for him when he

came to trial. After the amalgam was recovered, Bart appeared on November 17 before Superior

Court Judge C. V. Gottschalk at San Andreas. During his career as a highwayman, Black Bart robbed

twenty-eight stages; when he was caught he confessed to only the last and was sentenced on the

basis of that one alone. He received six years in San Quentin Prison.

Released from prison on January 21 of 1888, Charles E. Bolton disappeared from sight a few

weeks later and was never seen again. |

|